We may earn a commission from the affiliate links on this site. Learn more›

I’ve never loved maths. My brain doesn’t work that way.

But I love music, because it’s broad enough for all kinds of people. Across my student base, I see people who love the wild, imaginative side of music. Often, these people hate to read music; instead preferring to play intuitively, and they learn basically everything by ear.

Other students are attracted to the logic of music—the way that it holds together in numbers and patterns, and formulas which can be learned and replicated. These students are typically great at reading music, but aren’t so comfortable with improvisation.

New to drumming? Readers of Drumming Review can grab a free 30-day trial to Drumeo Edge! Don’t miss out!

Obviously I’m generalizing here, but most of us sit on a spectrum between these two extremes and usually, we’re closer to one of the edges than we are to the middle.

It’s okay to gravitate towards one of the poles, but if we want to embrace music for all it’s worth, it may be helpful to try and merge creative flair with a logical method (and vice versa).

Maybe there’ll be an article on improvisation for all you math heads before long, but until then, let’s talk counting!

This article is intended for beginners/intermediate players, but even if you’re a more advanced player, you might find some helpful reminders throughout the article.

Let’s Start From the Top

Most Western music is organized into blocks, which repeat or develop over the course of a piece. In popular music, we talk about intros, verses, choruses and outros – sections which return throughout a song, until the song finishes. In jazz and classical music, sections have different names: words like ‘head’ and ‘exposition’ are used to label the sections of a piece.

Whatever you call them, these sections of music are split into bars (sometimes called measures). There might be – for example – eight bars in a section, or twelve bars. In reality, there could be any number.

If we continue to dig, we’ll see that bars are divided into beats, and beats are divided into subdivisions.

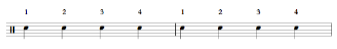

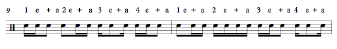

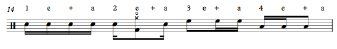

Here are two bars of quarter notes, and since we’re playing in a 4/4 time signature, each quarter note represents one beat:

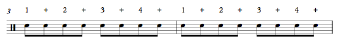

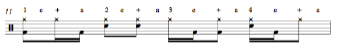

Now, we’ll split the beat into straight eighth notes across two bars:

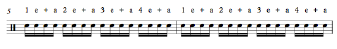

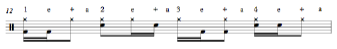

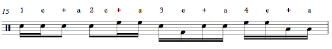

Next, we’ll split the beat into sixteenth notes across two bars (and remember, we pronounce the count ‘one ee and a, two ee and a’ etc):

Look at the labels above each of the examples. If you count aloud, perhaps to a metronome, you’ll see that beats 1, 2, 3 and 4 are in exactly the same place in the bar each time. We haven’t moved them anywhere, we’ve just split them into smaller, faster notes. These are the subdivisions that we mentioned earlier.

(Side note: you’ll notice that in the written examples, the numbers may have moved on the music — that’s because of the way music is laid out on a page. When you count aloud with a metronome, you’ll hear that the numbers are still heard In the same places.)

So far, so good.

Take a look at the two bar phrase below. I wonder if you’d feel confident reading it?

Perhaps you felt really comfortable with that, but if not try again, now that there are numbers above the notes (and remember to take it slow):

If that was your first try at counting while playing, I don’t know whether you found it noticeably easier to read the music or not. But hopefully it demonstrates a concept: counting in music is the same as measuring in DIY. Most people wouldn’t build furniture from scratch, without using a ruler or a tape measure—the table or the chair would be bent out of shape! In the same way, it’s really helpful to count while reading, or while trying to learn tricky phrases.

It’ll stop you from having to guess how something goes by instinct alone; and it’ll keep your playing tight, accurate and in proportion, as you move through the notes.

Learning New Grooves

So, counting can help us to read and play new phrases of music.

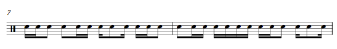

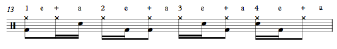

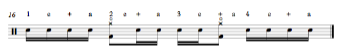

Let’s look at three, complete groove examples now. I’ve included the count above each one for your reference.

Notice again how beats 1, 2, 3 and 4 are still in the same place. They haven’t moved. They’re our anchor point. Each groove – however – contains a number of smaller, quicker subdivisions which give each phrase its unique sound. These are orchestrated onto the hi hat, the snare drum and the kick drum, but the notes still fall on particular beats which can be counted and identified accordingly – like coordinates on a map.

All Killer No Filler

In much the same way, you can see how reading a fill becomes easier as we count it through.

Learning by Ear

Counting isn’t just a reading tool, though. It’ll help with listening too. Maybe you’ve already had the experience of listening to a track, which you just can’t play along with. Perhaps you’ve listened to an mp3 and thought, “I can hear what the drummer is playing on this record but… I just can’t work out how to play it!”

Counting is the key to learning tricky passages by ear. Try listening to some music which you’d like to be able to play. Find a tricky phrase which you just can’t figure out by ear alone. Play it five times, and count ‘1 + 2 + 3 + 4 +’ along with it. It might be hard at first, because you still have to practice and learn to count well. But once you’ve mastered it, it takes all of the mystery out of playing a tricky phrase.

In this way, you have a formula at your finger tips for working out basically anything! Here are just three examples of things which become easier to play by ear, when we count:

Hit sections: these sometimes mystifying sections, which involve a whole band playing together to

accent certaln beats, are far easier to catch when you measure them with a count.

Time signatures: Trying to play to some music which doesn’t fit into a four count? Keep counting

in time with the music. Count beyond four if needed – until the current phrase seems to come to

natural conclusion. See which number you arrived at, and this will give you your time signature. It

takes practice, but when you’ve got it, you can work out any time signature at all.

Tricky phrases: sometimes we just can’t understand how to play a fill or a groove. Counting will

help us to master these with ease.

Creating New Phrases

Counting isn’t just for math nerds. It’s also a great tool for creating with confidence. It gives structure to our ideas, and enables us to work with variables which we can identity and change. For example, if you’re counting the sixteenth note subdivision:

‘1 e + a 2 e + a 3 e + a 4 e + a’,

You might notice that the kick drum sounds great on beat one; then again, you might decide to experiment by moving the same kick drum to the ‘e of 1’, instead. As you develop this process, you’ll see that it’s no longer up to your imagination alone to create new ideas: you’ll have a measurable foundation to build from, in a more methodical way. This is especially helpful because our imagination can tend to default towards creating music from muscle memory.

We tend to revert to familiar patterns and phrases which we re-emphasize, every time we play them. This can result in us feeling ‘stuck’ and unable to play anything outside of the same five or six ideas. By counting, we rely less on our instinct and more on an external process, which helps us to build new and exciting phrases of music.

Counting will also help when you create new fills. Just yesterday, I sat with a student who played some new fills without counting. They found it pretty hard to come back into a groove on beat one. When we count, it’s easier to make sure that we’re filling up each bar with the correct number of notes, so we end each fill at the right time.

Improvising

Counting is—in exactly the same way—great for improvising too. When we make grooves up, we spend time thinking about them. We hone them and practice them repeatedly. Maybe we’ll film ourselves playing a new groove or fill on a smartphone, and then listen back to it until we’re confident that we remember what to play. There’s planning involved in all of this.

Improvisation is creation which happens in real time. Here, there’s very little planning, repetition or practice. Rather, music is created and developed on the spur of the moment. If we’re used to counting and playing at the same time, we’ll be able to identify where we’re playing notes in each bar, and move the notes around accordingly. We’ll measure the structure of our improvising by counting, and be able to play around with that structure.

Practice Makes Perfect

Like anything, counting to four takes practice!

Okay, to be fair, you can probably count from one to four when you’re not drumming(!), but counting whilst playing at the same time is a whole different ball game. As always, it’s best to start slowly at first. Count out loud, with some simple grooves, and get used to that.

Eventually, you can switch to counting in your head; but counting aloud will still be a good tool to use, when playing a particularly tricky phrase. By speaking the numbers, we shift the job from our brain to our mouth, so that the brain can focus on the hard work of playing.

To Count, or Not to Count?

A builder doesn’t always use a hammer, and in the same way, a drummer needn’t always count. We’ll be able to play some phrases from intuition alone. Sometimes we ‘count with our instincts’ by feeling the pulse of the music in our body; and at other times, we move our head to the beat, and this provides a kind of count.

I once saw an interview with Michael Jackson, where he dismissed dancers who count too much. He thought that counting took away the ability to ‘dance by feel’. This might be true for drummers as well – I don’t know for certain, but I understand the point.

All the same, counting can – and should – be used in the right way, at the right time, to get the best from our playing. A road digger doesn’t have to use only a spade to do a good job—they can use drills too. So a drummer doesn’t have to use instincts alone, but can count as well.

And by the way, this shift between counting and not counting may happen mid song, mid-section or even mid-bar! When you become comfortable with your counting tool, you’ll be able to pick it up and put it down immediately, and without any fuss.

Outro

Some drummers love reading and some love to improvise. Wherever you fit on this spectrum, counting can help to make your playing more accurate, more creative and easier, too. It’s certainly possible to play by instincts alone, but it doesn’t necessarily make our playing any better.

If we never count, we can easily find ourselves stuck in a rut which is hard to break out of; as we repeat the same old grooves and fills, which flow from our muscle memory, rather than our thoughts. It can take a little getting used to, but counting is genuinely helpful. It can make us into better rounded players, who read confidentially, play accurately and work creatively.

Also, feel free to download and print this counting sheet for practicing!

About the Author

Chris Witherall is a pro drummer, producer and songwriter from London, England. He loves talking about music, and helping people to reach their music goals.